The Significance of Max Havelaar's Failure in His Attempt to Change the Colonial System

- liammagin133

- Jul 11, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Jul 30, 2025

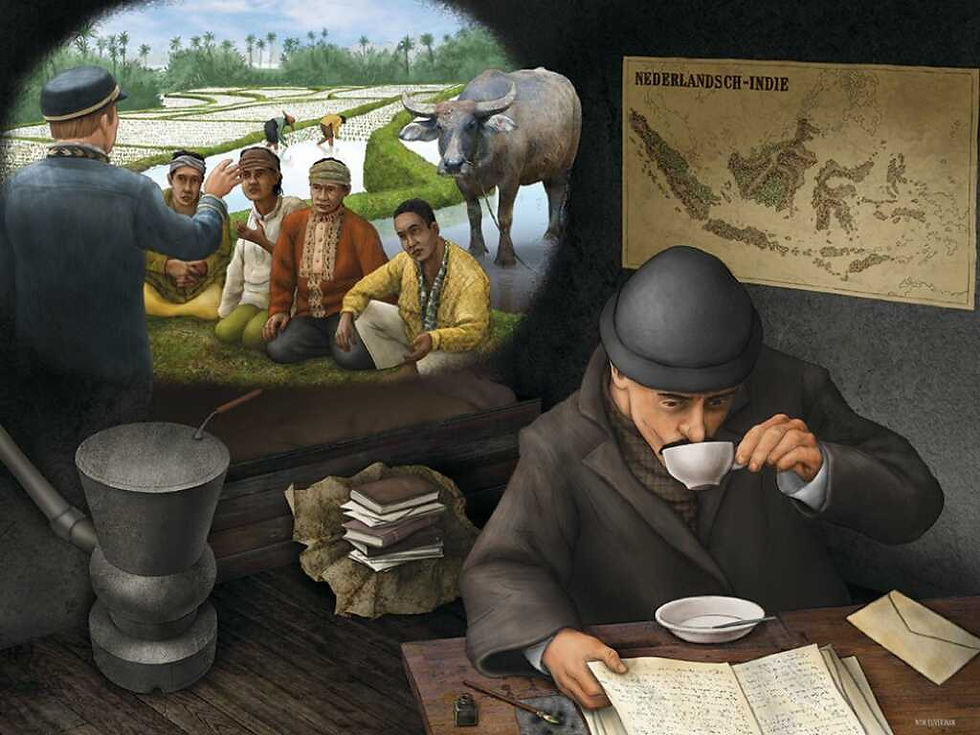

Recently, Donald Trump offered military support to Ukraine in exchange for natural resources. But as the novel Max Havelaar by Dutch author Multatuli (pseudonym of Eduard Douwes Dekker) demonstrates, liberation means little without a protected natural environment. Havelaar, the main character, who claims to stand for the colonised people, is a false Messiah. His desire to subjugate nature indeed reflects the strong colonial footprint of the Netherlands on its citizens and undermines his attempt to actually help the inhabitants of Lebak. Before I develop my analysis further, I will start with a brief summary of the book.

Here is a pdf version of the article, as well as a Dutch version of it:

The book begins with the Amsterdam coffee merchant Droogstoppel, who considers himself important and has little interest in literature or social issues. Through his acquaintance Sjaalman, he comes into possession of a manuscript, parts of which he decides to publish. He enlists his assistant Stern to convert the editable material into a book. The manuscript tells the story of Max Havelaar, an idealistic Dutch civil servant who is sent to Lebak on Java as assistant resident. There he discovers that the local population is being exploited by their own regent, Radhen Adhipatti Karta Nata Negara, and that the Dutch colonial government allows or even encourages this for economic reasons. Havelaar tries to raise the abuses with his superiors, especially with resident Slijmering, but his pleas fall on deaf ears. His attempts to bring justice are discouraged and ultimately thwarted, leading to his dismissal. The book ends with a fierce appeal from the author himself, Multatuli, who addresses the King of the Netherlands and demands an end to injustice in the Dutch East Indies.

Max Havelaar's lack of attention to nature undermines his attempt to change the colonial system. The description by Stern, the narrator of the section in which Havelaar is central, introduces him as a Messiah figure. When Havelaar addresses the Lebak chiefs, he is immediately described as such: ‘the images flow from his lips’, and when he interrupts his speech, people look at him and say ‘my God, who are you’ (85). In short, he speaks ‘like an apostle’ (85). It is interesting to note that religion is not used here as a direct colonial tool. Havelaar wants to be “gentle” and defend ‘the rights of the inhabitants of Lebak’ (182). Yet he does not want to abolish the colonial system, but to change it, which is an important nuance.

It is precisely his view of Lebak's nature that makes it clear that his mission is internally contradictory. His plans indeed reflect a shift from a colonial topos, ‘colonisation helps the colonised,’ to an anthropocentric topos, ‘the soil calls to us,’ which remains connected to colonisation. Havelaar says that the ‘fertile (...) soil calls for the grain it wants to give us’ (88). Furthermore, Havelaar is very aware of his prophetic dimension because he says that ‘Allah (...) wants it that way’ (88). According to Havelaar, one must use nature because God demands it. Havelaar, as a kind of prophet, takes control of nature as God's spokesperson and does not hesitate to kill snakes, for example, and give rewards in exchange (158). His use of nature is therefore paradoxical: he does it to strengthen the Lebak region economically, but in doing so he harms the Lebak people. Therefore, his resignation in chapter 20 is an inevitable consequence of his actions: not only the people but also nature must be helped in order to help the colonised.

In Max Havelaar, Multatuli not only addresses a colonial theme but also an ecological one, emphasising the interconnection between the two. Havelaar presents himself as a prophet who wants to help the Lebak people, but at the same time he is interested in using their land, which makes him a false Messiah. That is why his mission fails: his supposed desire for liberation is incomplete because it leaves no room for the autonomy of both people and nature. Some current world leaders would apparently do well to read the book.

© Liam Magin. All Rights Reserved. This work is the intellectual property of the author. Do not copy or redistribute without permission.

Bibliography:

Multatuli. Max Havelaar of De Koffiveilingen Der Nederlandse Handelsmaatschappy. Athenaeum - Polak & Van Gennep, 2010.

Comments